My Name is Roger, and I’m an alcoholic

In August 1979, I took my last drink. It was about four o’clock on a Saturday afternoon, the hot sun streaming through the windows of my little carriage house on Dickens. I put a glass of scotch and soda down on the living room table, went to bed, and pulled the blankets over my head. I couldn’t take it any more.

In August 1979, I took my last drink. It was about four o’clock on a Saturday afternoon, the hot sun streaming through the windows of my little carriage house on Dickens. I put a glass of scotch and soda down on the living room table, went to bed, and pulled the blankets over my head. I couldn’t take it any more.

On Monday I went to visit wise old Dr. Jakob Schlichter. I had been seeing him for a year, telling him I thought I might be drinking too much. He agreed, and advised me to go to “A.A.A,” which is what he called it. Sounded like a place where they taught you to drink and drive. I said I didn’t need to go to any meetings. I would stop drinking on my own. He told me to go ahead and try, and check back with him every month.

The problem with using will power, for me, was that it lasted only until my will persuaded me I could take another drink. At about this time I was reading The Art of Eating, by M. F. K. Fisher, who wrote: “One martini is just right. Two martinis are too many. Three martinis are never enough.” The problem with making resolutions is that you’re sober when you make the first one, have had a drink when you make the second one, and so on. I’ve also heard, You take the first drink. The second drink takes itself. That was my problem. I found it difficult, once I started, to stop after one or two. If I could, I would continue until I decided I was finished, which was usually some hours later. The next day I paid the price in hangovers.

I’ve known two heavy drinkers who claimed they never had hangovers. I didn’t believe them. Without hangovers, it is possible that I would still be drinking. Unemployed, unmarried, but still drinking–or, more likely, dead. Most alcoholics continue to drink as long as they can. For many, that means death. Unlike drugs in most cases, alcohol allows you to continue your addiction for what’s left of your life, barring an accident. The lucky ones find their bottom, and surrender.

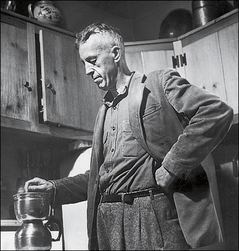

Bill W., co-founder of A.A.

An A.A. meeting usually begins with a recovering alcoholic telling his “drunkalog,” the story of his drinking days and how he eventually hit bottom. This blog entry will not be my drunkalog. What’s said in the room, stays in the room. You may be wondering, in fact, why I’m violating the A.A. policy of anonymity and outing myself. A.A. is anonymous not because of shame but because of prudence; people who go public with their newly-found sobriety have an alarming tendency to relapse. Case studies: those pathetic celebrities who check into rehab and hold a press conference.

In my case, I haven’t taken a drink for 30 years, and this is God’s truth: Since the first A.A. meeting I attended, I have never wanted to. Since surgery in July of 2006 I have literally not been able to drink at all. Unless I go insane and start pouring booze into my g-tube, I believe I’m reasonably safe. So consider this blog entry what A.A. calls a “12th step,” which means sharing the program with others. There’s a chance somebody will read this and take the steps toward sobriety.

Yes, I believe A.A. works. It is free and everywhere and has no hierarchy, and no one in charge. It consists of the people gathered in that room at that time, many perhaps unknown to one another. The rooms are arranged by volunteers. I have attended meetings in church basements, school rooms, a court room, a hospital, a jail, banks, beaches, living rooms, the back rooms of restaurants, and on board the Queen Elizabeth II. There’s usually coffee. Sometimes someone brings cookies. We sit around, we hear the speaker, and then those who want to comment do. Nobody has to speak. Rules are, you don’t interrupt anyone, and you don’t look for arguments. As we say, “don’t take someone else’s inventory.”

I know from the comments on an earlier blog that there are some who have problems with Alcoholics Anonymous. They don’t like the spiritual side, or they think it’s a “cult,” or they’ll do fine on their own, thank you very much. The last thing I want to do is start an argument about A.A.. Don’t go if you don’t want to. It’s there if you need it. In most cities, there’s a meeting starting in an hour fairly close to you. It works for me. That’s all I know. I don’t want to argue with you about it.

What a good doctor, and a good man, Jakob Schlichter was. He was in one of those classic office buildings in the Loop, filled with dentists and jewelers. He was a gifted general practitioner. An appointment lasted an hour. The first half hour was devoted to conversation. He had a thick Physician’s Drug Reference on his desk, and liked to pat it. “There are 12 drugs in there,” he said, “that we know work for sure. The best one is aspirin.”

One day, after a month of sobriety, I went to see him because I feared I had grown too elated, even giddy, with the realization that I need not drink again. “Maybe I’m manic-depressive,” I told him. “Maybe I need lithium.”

“Alcohol is a depressant,” he told me. “When you hold the balloon under the water and suddenly release it, it is eager to pop up quickly.” I nodded. “Yes,” I said, “but I’m too excited. I wake up too early. I’m in constant motion. I’d give anything just to feel a little bored.”

“Lois, will you be so kind as to come in here?” he called to his wife. She appeared, an elegant Jewish mother. “Lois, I want you to open a little can of grapefruit segments for Roger. I know you have a bowl and a spoon.” His wife came back with the grapefruit. I ate the segments. He watched me closely. “You still have your appetite,” he said. “When you feel restless, take a good walk in the park. Call me if it doesn’t work.” It worked. I knew walking was a treatment for depression, but I didn’t know it also worked for the ups.

Anyway, after I pulled the covers over my head, I stayed in bed until the next day, for some reason sleeping 13 hours. On the Sunday I poured out the rest of the drink which, when I poured it, I had no idea would be my last. I sat around the house not making any vows to myself but somehow just waiting. On the Monday, I went to see Dr. Schlichter. He nodded as if he had been expecting this, and said “I want you to talk to a man at Grant Hospital. They have an excellent program.” He picked up his phone and an hour later I was in the man’s office.

He asked me some questions (the usual list), said the important thing was that I thought I had a problem, and asked me if I had packed and was ready to move into their rehab program. “Hold on a second,” I said. “I didn’t come here to check into anything. I just came to talk to you.” He said they were strictly in-patient. “I have a job,” I said. “I can’t leave it.” He doubted that, but asked me to meet with one of their counselors.

This woman, I will call her Susan, had an office on Lincoln Avenue in a medical building across the street from Somebody Else’s Troubles, which was well known to me. She said few people stayed sober for long without A.A.. I said the meetings didn’t fit with my schedule and I didn’t know where any were. She looked in a booklet. “Here’s one at 401 N. Wabash,” she said. “Do you know where that is?” I confessed it was the Chicago Sun-Times building. “They have a meeting on the fourth floor auditorium,” she said. It was ten steps from my desk. “There’s one today, starting in an hour. Can you be there?”

She had me. I was very nervous. I stopped in the men’s’ room across the hall to splash water on my face, and walked in. Maybe thirty people were seated around a table. I knew one of them. We used to drink together. I sat and listened. The guy next to me got applause when he said he’d been sober for a month. Another guy said five years. I believed the guy next to me.

They gave me the same booklet of meetings Susan had consulted. Two day later I flew to Toronto for the film festival. At least here no one knew me. I looked up A.A. in the phone book and they told me there was an A.A. meeting in a church hall across Bloor Street from my hotel. I went to so many Toronto meetings in the next week that when I returned to Chicago, I considered myself a member.

That was the beginning of a thirty years’ adventure. I came to love the program and the friends I was making through meetings, some of whom are close friends to this day. It was the best thing that ever happened to me. What I hadn’t expected was that A.A. was virtually theater. As we went around the room with our comments, I was able to see into lives I had never glimpsed before. The Mustard Seed, the lower floor of a two-flat near Rush Street, had meetings from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., and all-nighters on Christmas and New Years’ eves. There I met people from every walk of life, and we all talked easily with one another because we were all there for the same reason, and that cut through the bullshit. One was Humble Howard, who liked to perform a dramatic reading from his driver’s license–name, address, age, color of hair and eyes. He explained: “That’s because I didn’t have an address for five years.”

When I mention Humble Howard, you are possibly thinking you wouldn’t be caught dead at a meeting where someone read from his driver’s license. He had a lot more to say, too, and was as funny as a stand-up comedian. I began to realize that I had tended to avoid some people because of my instant conclusions about who they were and what they would have to say. I discovered that everyone, speaking honestly and openly, had important things to tell me. The program was bottom-line democracy.

Yes, I heard some amazing drunkalogs. A Native American who crawled out from under an abandoned car one morning after years on the street, and without premeditation walked up to a cop and asked where he could find an A.A. meeting. And the cop said, “You see those people going in over there?” A 1960s hippie whose VW van broke down on a remote road in Alaska. She started walking down a frozen river bed, thought she herd bells ringing, and sat down to freeze to death. The bells were on a sleigh. The couple on the sleigh (so help me God, this is what she said) took her home with them, and then to an A.A. meeting. A priest who eavesdropped on his first meeting by hiding in the janitor’s closet of his own church hall. Lots of people who had come to A.A. after rehab. Lots who just walked in through the door. No one who had been “sent by the judge,” because in Chicago, A.A. didn’t play that game. “If you don’t want to be here, don’t come.”

Sometimes funny things happened. In those days I was on a 10 p.m. newscast on one of the local stations. The anchor was an A.A. member. So was one of the reporters. After we got off work, we went to the 11 p.m. meeting at the Mustard Seed. There were maybe a dozen others. The chairperson asked if anyone was attending their first meeting. A guy said, “I am. But I should be in a psych ward. I was just watching the news, and right now I’m hallucinating that three of those people are in this room.”

I’ve been to meetings in Cape Town, Venice, Paris, Cannes, Edinburgh, Honolulu and London, where an Oscar-winning actor told his story. In Ireland, where a woman remembered, “Often came the nights I would measure my length in the road.” I heard many, many stories from “functioning alcoholics.” I guess I was one myself. I worked every day while I was drinking, and my reviews weren’t half bad. I’ve improved since then.

There are no dues. You throw in a buck or two if you can spare it, to pay for the rent and the coffee. On the wall there may be posters with the famous 12 Steps and the Promises, of which one has a particular ring for me: “In sobriety, we found we know how to instinctively handle situations that used to baffle us.” There were mornings when I was baffled by how I was going to get out of bed and face the day.

I find on YouTube that there are many videos attacking A.A. for being a cult, a religion, or a delusion. There are very few videos promoting A.A., although the program has many. many times more members than critics. A.A. has a saying: “We grow through attraction, not promotion.” If you want A.A., it is there. That’s how I feel. If you have problems with it, don’t come. Is it a “religion?” The first three Steps are,

* Step 1 – We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable.

* Step 2 – Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

* Step 3 – Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understand Him.

The God word. The critics never quote the words “as we understood God.” Nobody in A.A. cares how you understand him, and would never tell you how you should understand him. I went to a few meetings of “4A” (“Alcoholics and Agnostics in A.A.”), but they spent too much time talking about God. The important thing is not how you define a Higher Power. The important thing is that you don’t consider yourself to be your own Higher Power, because your own best thinking found your bottom for you. One sweet lady said her higher power was a radiator in the Mustard Seed, “because when I see it, I know I’m sober.”

Sober. A.A. believes there is an enormous difference between bring dry and being sober. It is not enough to simply abstain. You need to heal and repair the damage to yourself and others. We talk about “white-knuckle sobriety,” which might mean, “I’m sober as long as I hold onto the arms of this chair.” People who are dry but not sober are on a “dry drunk.”

A “cult?” How can that be, when it’s free, nobody profits and nobody is in charge? A.A. is an oral tradition reaching back to that first meeting between Bill W. and Doctor Bob in the lobby of an Akron hotel. They’d tried psychiatry, the church, the Cure. Maybe, they thought, drunks can help each other, and pass it along. A.A. has spread to every continent and into countless languages, and remains essentially invisible. I was dumbfounded to discover there was a meeting all along right down the hall from my desk.

It prides itself on anonymity. There are “open meetings” to which you can bring friends or relatives, but most meetings are closed: “Who you see here, what you hear here, let it stay here.” By closed, I mean closed. I told Eppie Lederer, who wrote as Ann Landers, that I was now in the program. She said, “I haven’t been to one of those meetings in a long time. I want you to take me to one.” Her limousine picked me up at home, and we were driven to the Old Town meeting, a closed meeting. I went in first, to ask permission to bring in Ann Landers. I was voted down. I went back to the limo and broke the news to her. “Well I’ve heard everything!” Eppie said. “Ann Landers can’t get into an A.A. meeting!” I knew about an open meeting on LaSalle Street, and I took her there.

Eppie asked, “What do you think about my columns where I print the 20-part quiz to see if you have a drinking problem?” I said her quiz was excellent. I didn’t tell her, but at a meeting I heard a two-parter: If you drink when you didn’t intend to, and more than you intended to, you, my friend, have just failed this test.

“Everybody’s story is the same,” Humble Howard liked to say. “We drank too much, we came here, we stopped, and here we are to tell the tale.” Before I went to my first meeting, I imagined the drunks would sit around telling drinking stories. Or perhaps they would all be depressing and solemn and holier-than-thou. I found out you rarely get to be an alcoholic by being depressing and solemn and holier-than-thou. These were the same people I drank with, although now they were making more sense.

Pingback: I found a great post on Alcoholics Anonymous today… | Recovering Alcoholic